Predictable Placement and Restoration of Single Implants

Today’s technologies put greater control in the hands of clinicians

Bradley C. Bockhorst, DMD | Dean Saiki, DDS

Modern technologies, including cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), digital treatment planning, guided surgery, intraoral scanning, and CAD/CAM prosthetic fabrication, put a tremendous amount of control in the hands of clinicians who place implants. Not only do these tools allow implants to be placed and restored predictably and proficiently, but they also often enable clinicians to do so in a minimally invasive manner. This article offers a review of available technologies that can help provide successful outcomes for single-tooth replacement with implants.

Preoperative Examination

Case selection and treatment planning should begin with a thorough review of the patient’s medical and dental history. Any medical condition or medications that could affect wound healing should be taken into account. It is advisable that practitioners keep abreast of the latest recommendations regarding bisphosphonates and potential complications. When reviewing medications, clinicians should check with the patient regarding use of low-dose aspirin and supplements that can affect bleeding; because they are available over the counter, patients often overlook including them when listing their medications.

The clinical examination is used to determine the amount of available hard and soft tissues. It should include an evaluation of the prosthetic space and the amount of attached tissue in the edentulous area. Also, because guided drills are longer than standard drills, the patient’s vertical opening should be checked. A simple test is to place a guided drill into a handpiece and try it in the mouth. While a limited opening can be accommodated, it is better to be aware of it before going into a guided surgery.

The final decision of whether the patient is an implant candidate should be made after appropriate radiography is taken. The patient should be informed regarding the available restorative options, and, once a treatment plan is agreed upon, the procedure and proper informed consent should be documented.

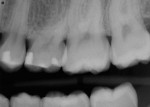

Documentation of the following case will be used to illustrate how technology can assist with the next stages, including implant planning and placement. A 24-year-old woman presented with a fractured retained deciduous maxillary molar (Figure 1). Her medical history and clinical examination were unremarkable. This type of case can be challenging in that the mesial-distal space is greater than that of a permanent second premolar. The goal was to maximize the bone below the sinus and place an implant parallel to the adjacent interproximal contacts in preparation for a screw-retained crown. Following extraction of the fractured molar, the site was allowed time to heal. Once healing occurred, the patient was sent for a CBCT scan.

CBCT and Digital Treatment Planning

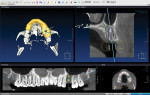

CBCT scans provide a method to obtain a 3-dimensional (3D) view of the patient’s anatomy with a much lower radiation dose than traditional spiral-beam CT scans.1,2 The CBCT scan can then be imported into digital treatment planning software. Vital anatomy such as the mandibular canals, mental foramina, sinuses, and adjacent teeth can be identified (Figure 2).

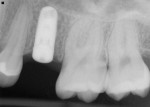

For partially edentulous cases, a preoperative intraoral scan of the patient or a scan of the model is merged into the planning software. This scan provides the soft-tissue information and will be used as the basis for the fabrication of the surgical guide. Virtual teeth or a scan of the diagnostic wax-up can be added to show the ideal position of the missing tooth. Knowing this information allows the implant(s) to be planned from both the surgical and prosthetic perspectives. A surgical guide can then be ordered and used to transfer the virtual plan to the clinical setting (Figure 3).3,4

Guided Surgery

Preoperatively, the patient is prescribed antibiotics, chlorhexidine, and pain medication. The antibiotic regimen and chlorhexidine rinses are started 2 days prior to surgery. While there is continued discussion/debate on antibiotics for implant surgery ranging from prescribing no antibiotics to a loading dose to a regimen of 7 to 10 days, at the time of this study the authors’ standard regimen was 10 days of amoxicillin 500 mg three times a day starting 2 days before surgery. The goal is to have the antibiotic on board at least 1 day before surgery. At the time of surgery, appropriate local anesthesia is administered. The patient rinses with chlorhexidine to decrease the bacteria count, and is then draped. A sterile technique is followed and appropriate precautions are taken.

Surgical Protocol

First, complete seating of the surgical guide is verified. Then, utilizing the appropriate key, the pilot drill is drilled to depth. If necessary, the surgical guide can be removed, the pilot drill placed back into the osteotomy, and a periapical radiograph taken to verify the initial site.

A tissue punch guide is then placed into the pilot hole. The diameter of the tissue punch guide and tissue punch should be based on the diameter of the planned healing abutment. Once the tissue plug is removed, the surgical guide is replaced. The osteotomy is completed using the appropriate guided drills and keys. The surgical guide is removed and the implant is threaded into place. Typically, the implant placement is started with the handpiece driver set at 35 Ncm instead of 50 Ncm due to the softer maxillary bone. Final seating is done by hand for more control, and the final torque value is recorded. The authors typically do not immediately temporize posterior teeth, but the rule of thumb followed is: <15 Ncm, place a cover screw; 15 Ncm to 35 Ncm, place a healing abutment; >35 Ncm, immediate temporization is an option.

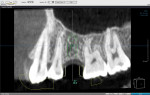

A healing abutment is used that flares to a similar diameter as that of the tooth to be replaced. The height should be approximately 1 mm above the soft-tissue crest upon placement. The threads of the healing abutment are coated with an antibiotic ointment and the abutment tightened to 15 Ncm. A postoperative radiograph is taken to verify complete seating (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Postoperative Instructions and Follow-Up

Postoperative instructions include directions for finishing the antibiotics and maintaining proper hygiene. The patient is encouraged to go on a soft diet and chew on the opposite side of his or her mouth for 2 weeks. Pain medication can be taken as needed; a small quantity (five tablets) of Vicodin 300 mg and ibuprofen 600 mg are prescribed. The patient is instructed to take one ibuprofen before the anesthetic wears off, then 1 tablet every 6 hours as needed for pain. If needed, the ibuprofen could be staggered with the Vicodin. Because these cases are done using a flapless technique, typically only ibuprofen is needed.

The patient is scheduled for a 1-week follow-up check. As long as there are no complications, patients are scheduled 3 months postoperatively to begin restoration. Although there is a trend to load implants sooner, if not immediately,5,6 the authors prefer a more conservative approach in cases with molars.

Digital Impressions

Once the case is ready to be restored, the healing abutment is removed and the sulcus and adjacent teeth, particularly the interproximal contact areas, are scanned. This should be done quickly to avoid soft-tissue collapse. When the objective is to provide a screw-retained crown, as in the case presented here, the interproximal contact areas of the adjacent teeth can be adjusted as needed; the goal is to have long-parallel interproximal contacts that are parallel to the implant line-of-draw.

Next, a scan body is mounted on the implant. A periapical radiograph is taken to verify complete seating. Quadrant scans of the implant arch and the opposing teeth are made. The final scan is of the bite. If the scan body is too tall, it should be removed and the healing abutment replaced for the bite scan.

The scans are merged in the CAD program, and a proposed crown is generated (virtual tooth or scan of a wax-up). Once the design is finalized (Figure 6), the selected block is placed and milled. The milled restoration is glazed and crystallized. If any custom staining is needed, the stain and glaze is done as a second firing. The titanium base is cemented to the completed crown and all excess bonding agent is removed.

Final Delivery

At final delivery, the healing abutment is removed and the screw-retained crown is seated. The interproximal and occlusal contacts are adjusted as needed. The abutment screw is tightened to 30 Ncm and a radiograph is taken to verify complete seating. Because the threads of the screw relax after the first tightening, the abutment screw is retightened to 30 Ncm if necessary. The second tightening gets closer to the desired torque value.

The head of the abutment screw is covered with Teflon tape, and the occlusal opening is sealed with resin-based composite. Post-delivery instructions are given, and the patient is put on an appropriate recall schedule (Figure 7 through Figure 9).

Discussion

A number of technologies and procedures were used in this report. It is up to the clinician to determine which of these to utilize in a particular case. A key to success in any case is appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning.7,8 The 3D view and diagnostic tools provided by CBCT scanning and digital treatment planning are invaluable.

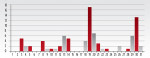

Between December 2012 and December 2015, the authors placed and restored a total of 86 implants (TSVT/TSVM, Zimmer Dental, www.zimmerdental.com) in 59 patients following the procedures as described above. A significant number (35%) of the implants were mandibular first molars. To date, no implants have been lost. Figure 10 shows the distribution of implants by location. While complications were rare, a few healing abutments did come loose during the osseointegration period. In those instances, if the soft tissue had collapsed, a laser or tissue punch was used to perform a mucoplasty and the healing abutment was tightened to 15 Ncm. One abutment screw fractured; it was retrieved and the restoration replaced.

Creating an osteotomy and threading in an implant is relatively simple; however, placing the implant in an incorrect position can be disastrous. The use of a surgical guide removes much of the stress of the procedure. Surgical guide usage is gaining popularity as prices and fabrication turnaround times decrease. The following suggestions for guided implant surgery are recommended:

If there is limited vertical opening, start with a shorter standard length drill and work up to a longer guided drill as needed. If necessary, the drill key can be placed on the drill and then seated in the surgical guide.

Trust, but verify. Digital treatment planning guided surgery systems are highly accurate, but as with any other procedure, potential exists for error every step of the way. In partial edentulous cases where the surgical guide can be easily removed and replaced, a periapical radiograph can be taken to verify the position and depth at any time.

The decision to do a flapless procedure should be based on whether bone grafting is needed and if the amount of attached tissue is adequate. In cases where it is feasible, a flapless procedure provides a minimally invasive approach. Not reflecting a flap results in very little postoperative discomfort and less potential bone lost, because the periosteum is not disrupted.9,10

Another issue involves temporization. While, as mentioned earlier, there is growing popularity to immediately temporize implants,5,6 many cases in the authors’ study were molars in mature sites. Therefore, they were not immediately provisionalized.

Finally, an advantage of screw-retained crowns, as opposed to cemented restorations, is the elimination of the risk of excess cement.11,12 Screw-retained restorations are also easily retrievable if needed. There are cases where a custom abutment and a separate crown are necessary. This is typically in the anterior maxilla where the trajectory of the abutment screw would be through the facial of the crown.

Conclusion

Although full-arch cases can be very rewarding, most implants placed today are used to restore single missing teeth. As the population ages, the need for single-tooth replacement will increase. Various technologies and procedures are currently available that provide clinicians the tools to predictably and proficiently place and restore implants. The key is to understand the technologies and their limitations. Appropriate training is needed to perform these techniques. Integrating these technology-driven procedures into a practice can be professionally rewarding and can provide patients with valuable, state-of-the-art service.

Disclosure

Bradley C. Bockhorst, DMD, and Dean Saiki, DDS, have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

References

1. Kosinski T. Optimizing implant placement and aesthetics: technology to the rescue! Dent Today. 2009;28(8):72-76.

2. Ganz SD. CT scan technology: an evolving tool for avoiding complications and achieving predictable implant placement and restoration. International Magazine of Oral Implantology. 2001;1(1):6-13.

3. Rosenfeld A, Mandelaris G, Tardieu PB. Prosthetically directed implant placement using computer software to ensure precise placement and predictable prosthetic outcomes. Part 1: diagnostics, imaging, and collaborative accountability. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2006;26(3):215-221.

4. Widmann G, Bale RJ. Accuracy in computer-aided implant surgery—a review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21(2):305-313.

5. Degidi M, Piattelli A. Comparative analysis study of 702 dental implants subjected to immediate functional loading and immediate nonfunctional loading to traditional healing periods with a follow-up of up to 24 months. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2005;20(1):99-107.

6. Ganeles J, Wismeijer D. Early and immediately restored and loaded dental implants for single-tooth and partial-arch applications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004;19 suppl:S92-S102.

7. Kois JC. Predictable single-tooth peri-implant esthetics: five diagnostic keys. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2004:25(11):895-900.

8. Jansen CE, Weisgold A. Presurgical treatment planning for the anterior single-tooth implant restoration. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1995;16(8):746-754.

9. Bashutski JD, Wang HL, Rudek I, et al. Effect of flapless surgery on single-tooth implants in the esthetic zone: a randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84(12):1747-1754.

10. Fortin T, Bosson JL, Isidori M, Blanchet E. Effect of flapless surgery on pain experienced in implant placement using an image-guided system. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006;21(2):298-304.

11. Goodacre CJ, Bernal G, Rungcharassaeng K, Kan JY. Clinical complications with implants and implant prostheses. J Prosthet Dent. 2003;90(2):121-132.

12. Strong SM. What’s your choice: cement- or screw-retained implant restorations? Gen Dent. 2008;56(1):15-18.

Bradley C.

Bockhorst, DMD

Private Practice

Oceanside, California

Dean Saiki, DDS

Private Practice

Oceanside, California